ESTATES-GENERAL OF 1789

IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

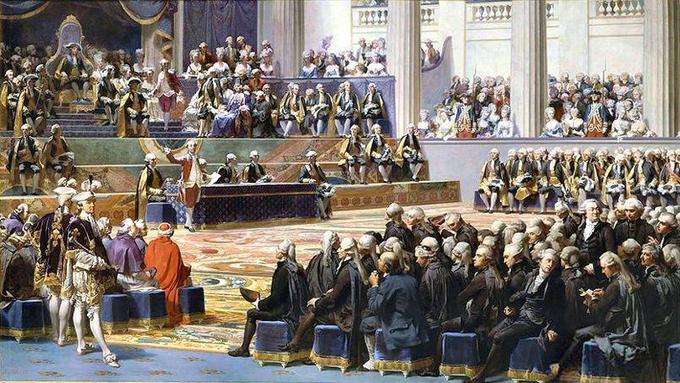

The Estates-General was a meeting of the three estates within French society which included the clergy, nobility and the peasant classes. The estate to which a person belonged was very important because it determined that person’s rights, obligations and status. Members of the Roman Catholic clergy, who numbered about 100,000, made up the first estate. The clergy included people such as: monks, nuns, parish priests and bishops. The church had many privileges in French society, including the collection of tithes. Tithes are one-tenth of a person’s income which is formally taken in support of the church and clergy. Also, the Church did not pay land taxes, even though it owned about 6% of the land and was very wealthy.

Louis XVI

Louis XVI

The second estate consisted of the French nobility, which numbered about 400,000 people. The nobles owned about 20% of the land and had many feudal privileges. For example, they were exempt from paying many taxes and were allowed to collect dues from the peasants. The nobility occupied most of the powerful positions in the army, Church and government.

All other people in France, about 97% of the population belonged to the third estate. This group included: merchants, lawyers, poor laborers, and ordinary peasants. They paid most of the taxes collected by the government but were generally looked down upon by the nobility. They resented the power of the Church and the nobility.

Louis XVI called the Estates-General in May of 1789, the first since 1614, in hopes of helping to advise him on the economic and agricultural crisis that France was facing in the years before the French Revolution. The Estates-General included 303 delegates for the clergy, 282 delegates for the nobility, and 578 delegates for the peasant class.

All other people in France, about 97% of the population belonged to the third estate. This group included: merchants, lawyers, poor laborers, and ordinary peasants. They paid most of the taxes collected by the government but were generally looked down upon by the nobility. They resented the power of the Church and the nobility.

Louis XVI called the Estates-General in May of 1789, the first since 1614, in hopes of helping to advise him on the economic and agricultural crisis that France was facing in the years before the French Revolution. The Estates-General included 303 delegates for the clergy, 282 delegates for the nobility, and 578 delegates for the peasant class.

Jacques Necker

Jacques Necker

Immediately, the goal of the meeting was to deal with France’s financial crisis. Louis XVI’s ministers, including the popular Jacques Necker, spoke only about the financial situation facing the country and otherwise stayed with protocol on how to carry out the Estates-General. Traditionally, voting would occur with each estate or order having one vote to represent the entire estate. This would mean that the first estate would receive one vote, the second estate would receive one vote and the third estate would receive one vote. However, this angered the representative of the third estate who preferred a system in which each representative would receive one vote.

The third estate feared that if the representatives voted by order then the clergy and nobility would overrule them on every vote and the third estate would have no power in the meeting. At the same time, the first and second estates feared losing some of their privilege to the third estate if the voting was changed such that each representative voted. Since the third estate nearly double the representatives of the other two estates, it was feared that the third estate could overrule the other two on important matters. This is exactly what the third estate was counting on. Representatives of the third estate also believe that some poorer priests of the first estate would vote alongside them, consider their financial position.

In the end, the Estates-General reached an impasse in which they could not come to agreement about how to carry out the voting of the meeting. In response, the third estate carried out their own discussions and established themselves as the National Assembly, and sought to work with or without the other two estates. Louis XVI tried to halt the actions of the third estate by commanding an end to the Estates-General and forcing each estate to separate. Famously, the National Assembly responded by moving their discussions to the nearby tennis court where they took the “Tennis Court Oath”. The Estates-General had failed and the first steps of the French Revolution had been taken.

The third estate feared that if the representatives voted by order then the clergy and nobility would overrule them on every vote and the third estate would have no power in the meeting. At the same time, the first and second estates feared losing some of their privilege to the third estate if the voting was changed such that each representative voted. Since the third estate nearly double the representatives of the other two estates, it was feared that the third estate could overrule the other two on important matters. This is exactly what the third estate was counting on. Representatives of the third estate also believe that some poorer priests of the first estate would vote alongside them, consider their financial position.

In the end, the Estates-General reached an impasse in which they could not come to agreement about how to carry out the voting of the meeting. In response, the third estate carried out their own discussions and established themselves as the National Assembly, and sought to work with or without the other two estates. Louis XVI tried to halt the actions of the third estate by commanding an end to the Estates-General and forcing each estate to separate. Famously, the National Assembly responded by moving their discussions to the nearby tennis court where they took the “Tennis Court Oath”. The Estates-General had failed and the first steps of the French Revolution had been taken.

CITE THIS ARTICLEAUTHOR

|

|