AZTEC ECONOMY

|

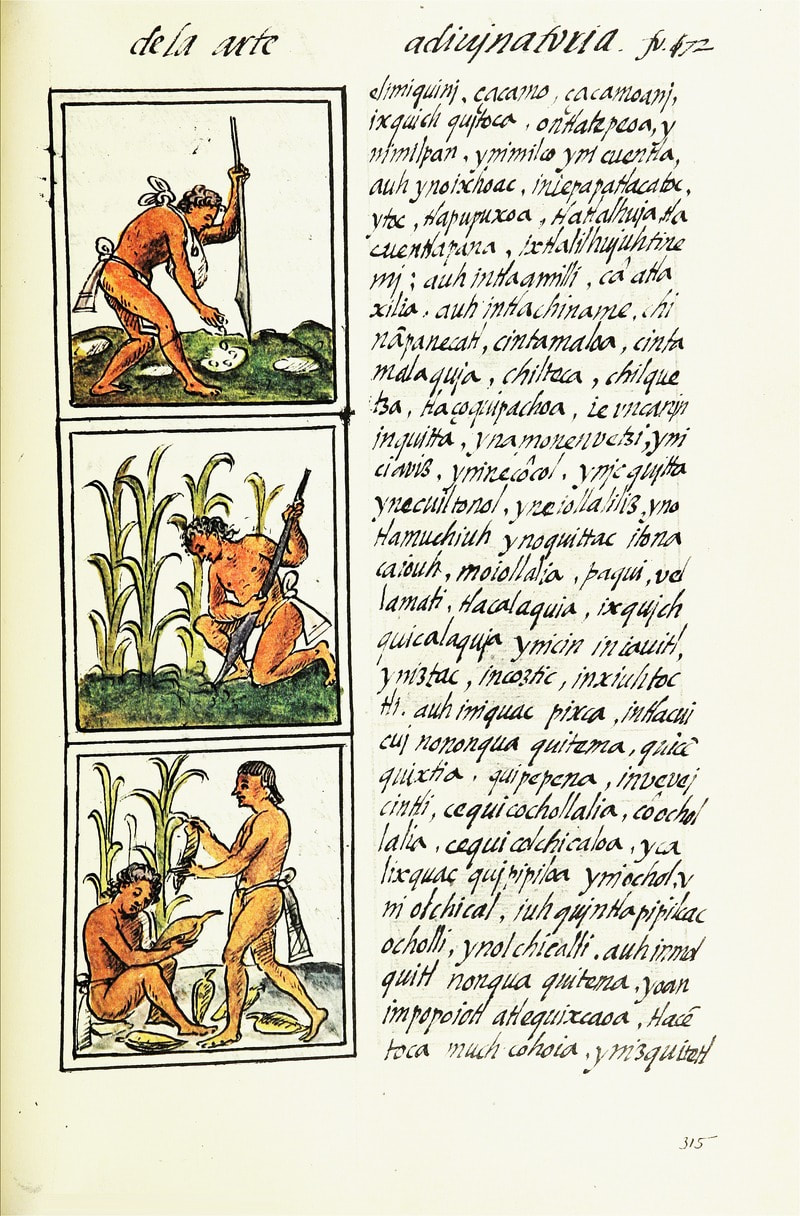

The Aztec Empire had a strong and thriving economy before the arrival of Spanish conquistadors in 1519. Due to its island location the Aztec economy was based primarily on agriculture in the form of chinampas. Also referred to as ‘floating gardens’ chinampas were mounds of dirt and other debris built up in the shallow, swampy areas of Lake Texcoco which surrounded Tenochtitlan. The use of chinampas was particularly popular in southern area of Lake Texcoco near the altepetl of Xochimilco. It was a common practice throughout Mesoamerica but the Aztec Empire was the first to use the farming technique on a mass scale. The Aztec farmers had to follow a few key points to create the chinampas. First, the farmers would use wooden stakes to section off the area they were going to build up. Next, they would use vines to create a fence like structure under the water between the stakes. Finally, they would fill the fenced off area with dirt and vegetation to build it up above the surface of the water. Sometimes trees were planted on the edges of the chinampas such that their roots could anchor the dirt and prevent the mounds from shifting. Then the farmers would plant crops such as corn (maize) in the fertile mounds of dirt. When combined with other forms of farming such as traditional farms and terraced hill sides, the agriculture of Aztec Empire grew dramatically and became a central component of the economy.

|

Another important aspect of the Aztec economy was the tribute system present throughout much of Mesoamerica. Following the Aztec’s founding and construction of Tenochtitlan in the Valley of Mexico in 1325, they quickly established their authority across the other societies in the valley. At the time the Valley of Mexico was populated by many different powerful civilizations, including: Chalco, Tepanec, Tlacopan, Texcoco, Culhuacan, and Chichimec. Several of these civilizations were also on the shores of Lake Texcoco, including the Culhuacan which were on the south shore. By conquering many of these other city-states the Aztec were able to force them to pay tribute back to Tenochtitlan.

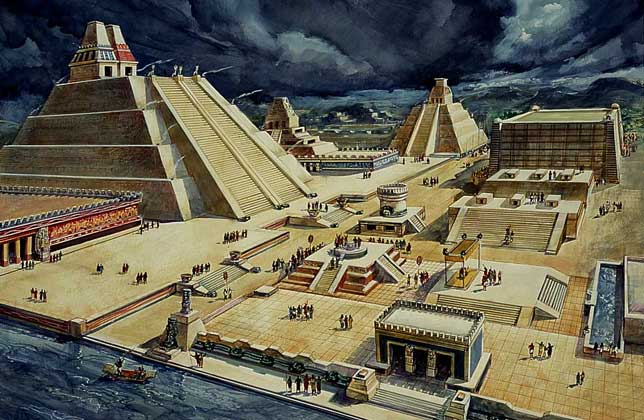

All of the Aztec rulers at this time pushed forward with expanding the Aztec Empire across Mexico and strengthening the power of Tenochtitlan. In fact, the city grew in size and importance during this time as the Aztec culture came to dominate the region. For example, by the early 16th century, Tenochtitlan is estimated to have been three to five square miles (eight to thirteen square kilometers), and have a population of between 200,000 and 300,000 people. This means that it was one of the largest cities in the world at the time and larger than any in Europe. As well, the Aztec Empire had spread far from the Valley of Mexico during this time and, at its height, the empire consisted of land across most of central Mexico including the coastlines in both the Gulf of Mexico and Pacific Ocean. This vast expansion meant that the Aztec had conquered and suppressed many different groups of Mesoamerican peoples. The Aztec controlled these different societies by forcing them to provide tributes for payment and ritual sacrifice.

|

For example, conquered city-states, which are referred to as ‘altepetl’, were allowed to maintain their current rulers and religion so long as they met several requirements, including: support the Aztec Empire and tlatoani of Tenochtitlan, pay tribute to Tenochtitlan, and include the Aztec god Huitzilopochtli in their own religious beliefs and practices.

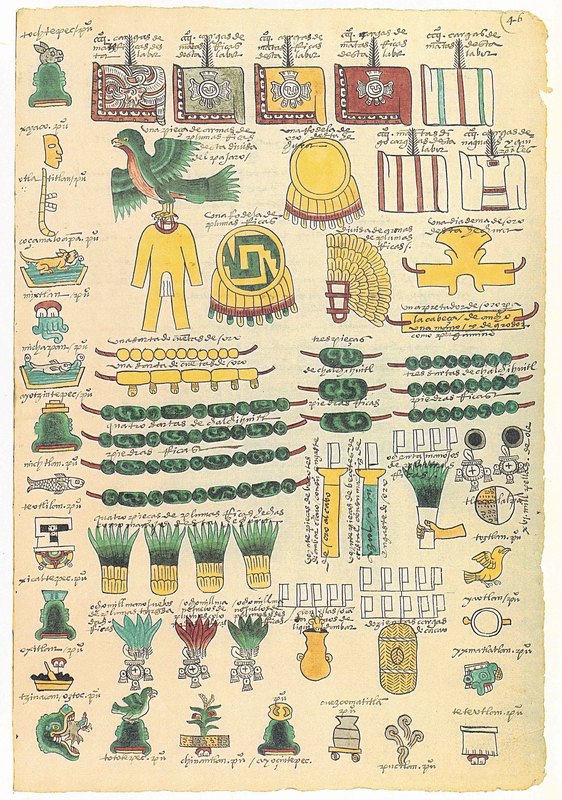

This system of tribute provided the Aztec Empire, and ultimately Tenochtitlan, with a continuous supply of goods and people from across central Mexico. In terms of people, conquered altepetl would often supply Tenochtitlan with either warriors or slaves. However, the supply of goods was vast and powered the Aztec economy. Goods paid as tribute to the Aztec included: food, clothing, weapons, luxury items, metals, lumber and more. These tributes were paid to the leader, huey tlatoani of the Aztec, who would then redistribute it throughout the society of Tenochtitlan. This was important because it gave the huey tlatoani a great deal of power. For example, he could use the incoming tribute as a means of securing loyalty and favor from powerful nobles in the Aztec society. The tribute system benefitted the overall economy of the Aztec because it promoted trade and transport between the different city-states in the region which led to new businesses and a merchant class. |

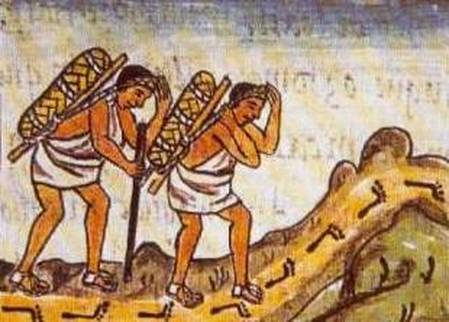

Another key feature of the economy was the development of large markets for the different goods from across the Aztec Empire. These markets supplied the citizens with different foods, luxury items and crafts. The markets sold all sorts of things, but it greatly benefitted both merchants (traders) and artists and craftspeople. For example, it allowed the artists and craftspeople a venue to sell their finely crafted goods. As well, the traders helped distribute goods across the Aztec Empire and ultimately central Mexico. For instance, all goods were transported throughout the empire by human beings. This was because the Aztec lacked any large domesticated animals such as horses. As such, waterways were important to Aztec trade because it allowed goods to be moved quickly. The class of people who carried out this long distance trade in the Aztec Empire were referred to as ‘pochteca’. They organized trade across the empire and held a high position in society because of it. They were also sometimes known to act as spies for the tlatoani since their travels sometimes took them into enemy territory. The largest market in the Aztec Empire was in Tenochtitlan in a region referred to as Tlatelolco. While in the city, Hernán Cortés, wrote extensively about what he witnessed in a series of letters referred to as the ‘Letters from Mexico’. In his ‘Second Letter from Mexico’ described the market of Tenochtitlan as follows:

“There is one square twice as large as that of the city of Salamanca, surrounded by porticoes, where are daily assembled more than sixty thousand souls, engaged in buying, and selling; and where are found all kinds of merchandise that the world affords, embracing the necessaries of life, as for instance articles of food, as well as jewels of gold and silver, lead, brass, copper, tin, precious stones, bones, shells, snails, and feathers. There are also exposed for sale wrought and unwrought stone, bricks burnt and unburnt, timber hewn and unhewn, of different sorts. There is a street for game, where every variety of birds found in the country are sold, as fowls, partridges, quails, wild ducks, fly-catchers, widgeons, turtle-doves, pigeons, reedbirds, parrots, sparrows, eagles, hawks, owls, and kestrels they sell likewise the skins of some birds of prey, with their feathers, head, beak, and claws. There are also sold rabbits, hares, deer, and little dogs, which are raised for eating and castrated. There is also an herb street, where may be obtained all sorts of roots and medicinal herbs that the country affords. There are apothecaries' shops, where prepared medicines, liquids, ointments, and plasters are sold; barbers' shops, where they wash and shave the head; and restaurateurs, that furnish food and drink at a certain price. There is also a class of men like those called in Castile porters, for carrying burdens. Wood and coals are seen in abundance, and braziers of earthenware for burning coals; mats of various kinds for beds, others of a lighter sort for seats, and for balls and bedrooms. There are all kinds of green vegetables, especially onions, leeks, garlic, watercresses, nasturtium, borage, sorrel, artichokes, and golden thistle; fruits also of numerous descriptions, amongst which are cherries and plums, similar to those in Spain; honey and wax from bees, and from the stalks of maize, which are as sweet as the sugar-cane; honey is also extracted from the plant called maguey, which is superior to sweet or new wine; from the same plant they extract sugar and wine, which they also sell. Different kinds of cotton thread of all colors in skeins are exposed for sale in one quarter of the market, which has the appearance of the silk-market at Granada, although the former is supplied more abundantly. Painters' colors, as numerous as can be found in Spain, and as fine shades; deerskins dressed and undressed, dyed different colors; earthenware of a large size and excellent quality; large and small jars, jugs, pots, bricks, and an endless variety of vessels, all made of fine clay, and all or most of them glazed and painted; maize, or Indian corn, in the grain and in the form of bread, preferred in the grain for its flavor to that of the other islands and terra-firma; pâtés of birds and fish; great quantities of fish, fresh, salt, cooked and uncooked ; the eggs of hens, geese, and of all the other birds I have mentioned, in great abundance, and cakes made of eggs.”

While many goods were traded at the markets, one of the most significant was the cacao bean, which is used to make chocolate. In fact, chocolate had a long history of use by Mesoamerican people dating back over thousands of years. The cacao bean (of which chocolate is made from) is native to Mesoamerican and as such, was an important resource for many different Mesoamerican people, including: Olmec, Mayan, and Aztec. For example, the word chocolate comes from the Nahuatl (language of the Aztec) word ‘chocolātl’. When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in Aztec territory in 1519, they noted that the Aztec emperor Moctezuma II and other nobles would consume a chocolate drink. The chocolate drink was mixed with spices and maize. Moctezuma II was said to drink dozens of cups of it each day. Chocolate was surprising for the Spanish, since the cacao bean had only ever grown in the New World prior to the arrival of Europeans in the 15th and 16th centuries. Eventually, the Spanish took the cacao bean back to Europe with them and it has since spread worldwide. Europeans were the ones who added sugar to the chocolate drink that led to modern forms of hot chocolate. Beyond use as a drink, the cacao bean was also an important factor in the Aztec economy. For the Aztecs the cacao beans were viewed as a gift from the god Quetzalcoatl and were held in high value. As a result, the cacao bean was used as a form of currency in the Aztec Empire. For instance, Aztec traders and merchants would use it to carry out the exchange of goods in the different markets across the Aztec Empire.

CITE THIS ARTICLEAUTHOR

|

|