CHILD LABOR IN THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

The Industrial Revolution was a major event in world history and had a profound effect on societies around the world. In particular, the Industrial Revolution impacted the lives of working class people and the children of industrial societies. Child labor was a common feature in industrial societies as children as young as four years old were often employed in the factories and mines that developed during the time. This was particularly true in Britain, where the Industrial Revolution first began in the 1700s.

Child labor was especially common in the late 18th century, during the early years of the Industrial Revolution. At the time, industrial cities and towns grew dramatically due to the migration of farmers and their families who were looking for work in the newly developed factories and mines. The living conditions in the cities and towns were miserable and characterized by: overcrowding, poor sanitation, spread of diseases, and pollution. As well, workers were paid low wages that barely allowed them to afford the cost of living associated with their rent and food. As a result, many of these working-class families needed the extra income that their children earned while working.

|

For their part, factory owners wanted to employ children for several reasons. First, children generally made considerably less than adults did for doing the same work. For example, some estimates show that children were paid between 10-20% that of an adult. Therefore, the owners saved money by employing children. Second, children were generally more obedient than adults in terms of completing work and accepting punishment. Factory overseers, who were employed as managers of the factory floor, were known to whip or beat employees that were late for work. For example, in an interview in 1819, John Fairbrother commented that he had seen his master “with a horse whip standing outside the mill when the children have come too late [and] he lashed them all the way to the mill.” Therefore, the factory owners hired children because they were easier to control and more likely to accept punishment. Whereas, an adult made have resisted or fought back. Finally, children were hired during the Industrial Revolution because they naturally smaller and could fit into tighter spaces. This was especially important in the new mechanized factories of the late 18th century. For example, textile mills had machinery that spun thread at high speeds. Sometimes these machines jammed or became clogged. The small fingers and hands of the children were ideal for unclogging these machines, which made children important in the production process. Therefore, factory owners employed children because it helped in the production of goods.

|

The factories and mines of the late 18th century and early 19th century were dangerous and unforgiving places to work in. The working conditions that working-class people faced were known to include: long hours of work (12-16 hour shifts), low wages that barely covered the cost of living, and workplaces with little or no rights. These conditions were difficult for all workers but especially so for children. As such, children often faced incredible hardships and suffered abuse in the workplace. To better understand the situation, its first important to understand the political ideology of the time, which historians refer to as classical liberalism. Classical liberalism is an ideology characterized by laissez-faire capitalism, which means that the government played as little a role in the economy as possible. As a result, there were little to no rules in place for workers in the Industrial Revolution, and the wealthy owners could act in any manner that they wanted. For example, the factories and mines were incredibly dangerous places with very few safeguards.

|

Spinning machines in textile mills were often left unguarded and posed a serious risk. For instance, a report from the British House of Commons in 1832 commented that “There are factories, no means few in number, nor confined to the smaller mills, in which serious accidents are continually occurring, and in which, notwithstanding, dangerous parts of the machinery are allowed to remain unfenced.” This situation caused children to become injured, as they were working dangerously close to spinning belts and shafts that powered the machines. Furthermore, children were often required to work on machines that they were not tall enough to operate safely. For example, in the image to the left the boy is too short to operate the machine and must stand on top of it in order to reach the spindles. As well, in the image a large spinning belt is clearly shown and it is not guarded. Any loose fitting clothing could easily become clogged and pull him violently into the workings of the machine. This possibility was best evidenced in the 1828 Memoir of Robert Blincoe by John Brown.

|

|

In the memoir he recounts witnessing a scene of horror. “A girl named Mary Richards, who was thought remarkably pretty when she left the workhouse, and, who was not quite ten years of age, attended a drawing frame, below which, and about a foot from the floor, was a horizontal shaft, by which the frames above were turned. It happened one evening, when her apron was caught by the shaft. In an instant the poor girl was drawn by an irresistible force and dashed on the floor. She uttered the most heart-rending shrieks! The factory overseer ran towards her, an agonized and helpless beholder of a scene of horror. He saw her whirled round and round with the shaft - he heard the bones of her arms, legs, thighs, etc. successively snap asunder, crushed, seemingly, to atoms, as the machinery whirled her round, and drew tighter and tighter her body within the works, her blood was scattered over the frame and streamed upon the floor, her head appeared dashed to pieces - at last, her mangled body was jammed in so fast, between the shafts and the floor, that the water being low and the wheels off the gear, it stopped the main shaft. When she was extricated, every bone was found broken - her head dreadfully crushed. She was carried off quite lifeless.” These types of situations occurred because children were given clothing that did not fit. Also, as shown in the earlier image, they were sometimes required to operate machines without any protection at all, such as shoes.

|

Because children were small and could fit into tighter spaces, they were often tasked with unclogging machines that had stopped operating. As a result, children often suffered horrible injuries to their hands and fingers when the machines suddenly began working again. For example, a doctor from Manchester, England gave the following report in an 1819 interview. “When I was a surgeon in the infirmary, accidents were very often admitted to the infirmary, through the children's hands and arms having being caught in the machinery; in many instances the muscles, and the skin is stripped down to the bone, and in some instances a finger or two might be lost. Last summer I visited Lever Street School. The number of children at that time in the school, who were employed in factories, was 106. The number of children who had received injuries from the machinery amounted to very nearly one half. There were forty-seven injured in this way.” As his report suggests, the injuries that the children suffered were painful and disfiguring and relatively common.

Another hardship that many workers faced in the factories was the grueling heat produced by the numerous machines. Factories in the Industrial Revolution were cramped and contained spaces. Often times, they were built without windows or proper ventilation and as a result the machines would quickly cause the inside temperature of the factory to increase dramatically. For example, in 1824, William Cobbett, a British parliamentarian commented on his visit to a factory. “What… must be the situation of the poor children who are doomed to toil fourteen hours a day, in an average of eighty-two degrees? Can any man, with a heart in his body, and a tongue in his head, refrain from cursing a system that produces such slavery and such cruelty?”

Not only were children forced to work in hot, dangerous and cramped conditions, but if they were injured on the job they had little to no rights to receive compensation. Because the government practised laissez-faire capitalism, this meant that they did not have initiatives in place to force factories to protect workers or to compensate them when they became injured and could no longer work. For example, a report from the British House of Commons in 1832 commented that “workers are often abandoned from the moment that an accident occurs; their wages are stopped, no medical attendance is provided, and whatever the extent of the injury, no compensation is afforded.”

As well as working in factories, many children were also employed in coal mines. Coal was one of the key resources necessary for industrialization and one of the reasons that Britain was the first country to industrialize in the 1700s. As well, with the creation of the steam engine, coal became an even more important resource as it was used to power the factories and methods of transportation, such as: ships and trains. Children were used in coal mines to do all sorts of work. In general, their small bodies were ideal for going into deep channels in order to carry coal to the surface. This was a common job completed by children and involved them being connected to a coal cart by a strap so that they could pull the cart of coal behind them. As well, children were also used to sort coal and remove any impurities. Coal mining was difficult and dangerous work for children for several reasons, including: the mine shafts were constantly susceptible to collapse and the air quality was extremely poor and led to breathing problems.

In all, child labor was a common feature of the Industrial Revolution and involved children suffering under horrible and abusive conditions. Whether it was in factories, mines or other workplaces, children were expected to work in hot and dangerous conditions for low amounts of pay and long gruelling hours.

|

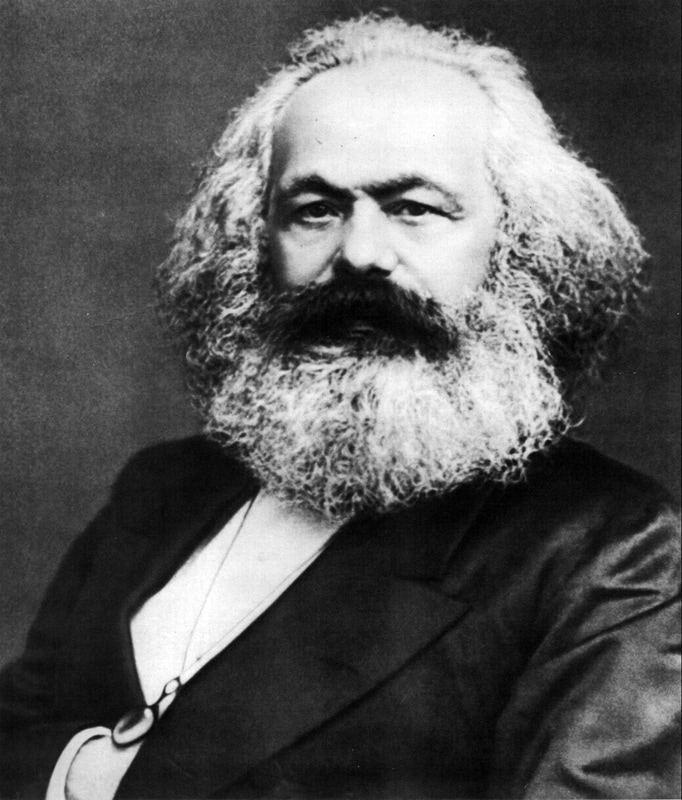

Eventually, people began to protest these conditions and argue that child labor should be outlawed or there should be limits placed upon the employment of children. In general, the movement to end child labor coincided with the rise of socialist ideologies such as utopian socialism and Marxism. For example, Robert Owen, a utopian socialist, believed it was important and necessary for business owners to operate profitable businesses that made them wealthy, he also believed it was important that the workers in these businesses were treated fairly. In his own mills, Owen improved the life of his employees in many ways including: creating a company store in which employees could buy goods, limiting the hours of workers, offering basic healthcare, and providing education for both children and adults. Karl Marx, the famous socialist writer, was also highly critical of child labor in the Industrial Revolution. In the Communist Manifesto, which is the book that he wrote with fellow socialist, Friedrich Engels, he discussed the failing of capitalism and classical liberalism in relation to how the poorest in society were taken advantage of by the richest. As such, he was critical of child labor in terms of it being an exploitation of the poor by the wealthy. Charles Dickens, the famous British playwright criticized the use of child labor in several of his plays, including: A Christmas Carol and Oliver Twist. Many of his writing were set in the timeframe of the Industrial Revolution and often questioned the gaps that existed between the wealthy and the working-class, especially in terms of how it impacted children in British industrial society.

|

The first major legislation created to place limits on child labor were a series of Factory Acts passed by the British parliament throughout the 1800s. These acts limited the number of hours that children could work and placed regulations on workplaces in terms of safety and cleanliness. For example, by 1819, the Factory Acts limited the workday for British children at 12 hours. By 1833, child labor was further regulated when it became illegal for children under 9 years old to work, and children under 13 were not allowed to work more than 9 hours a day.

CITE THIS ARTICLEAUTHOR

|

|

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION RESOURCES

Show More